The Next 85 Days Are Critical For Future-Proofing Beauty Supply Chains, According To Atelier’s Nick Benson

Whether a beauty brand generates $1 billion or $1, it can’t be disentangled from the global supply chain.

That’s because it’s practically impossible for some part of its business, whether ingredients, packaging, manufacturing, distribution or marketing, to avoid exposure to markets beyond its home base. Given the interconnected realities of producing and selling beauty products, President Donald Trump’s efforts to decouple the United States economy from the rest of the world has sent fear through the beauty industry. Although he paused the so-called reciprocal tariffs, which are levied on top of flat 10% tariffs on about 90 countries, last Wednesday for 90 days, the fear hasn’t evaporated because tariffs on China, the single biggest source of beauty manufacturing and packaging, remain up to 145%, and reciprocal tariffs could return.

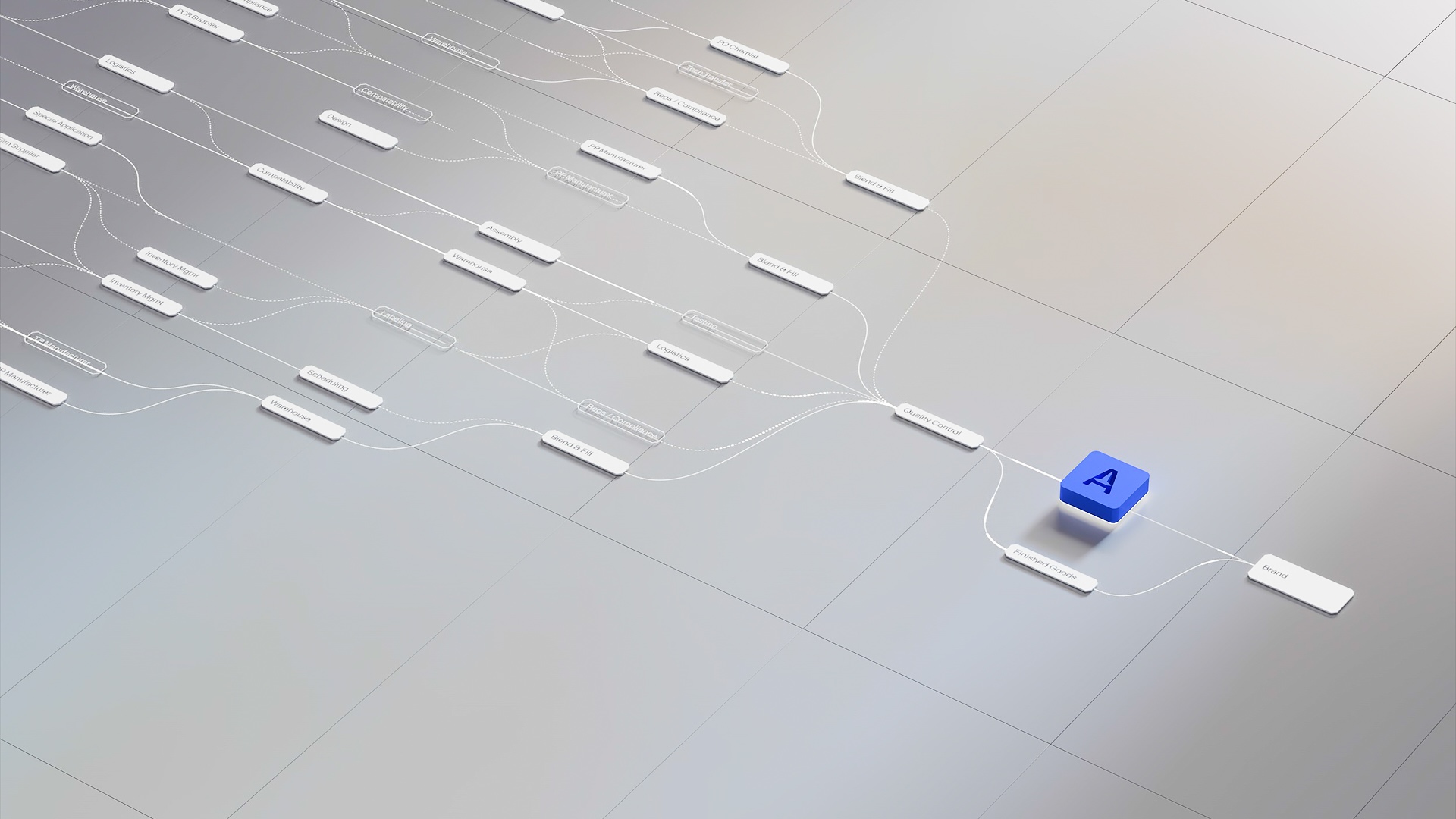

Over the next 90 days, Nick Benson, founder and CEO of Atelier, a product innovation and manufacturing platform sourcing supply chain partners for about 75 beauty companies, counsels brands to engage in serious internal soul searching about the state of their supply chain and the future of it rooted in their long-term business vision. Headquartered in Sydney and New York, Atelier, which charges brands the cost of the units it’s producing with them, has relationships with nearly 1,000 supply chain actors worldwide totaling $25 billion in beauty manufacturing capacity—the entire U.S. has $44 billion in beauty manufacturing capacity—and closed a $10 million series A funding round last year led by Macquarie Capital.

“Tariffs are just another nail in the coffin of global volatility. There’s been volatility in trade dynamics starting in 2016 with the trade war and then the COVID supply chain shock, even the ship turning sideways in the Suez Canal,” says Benson. “There seems to just be one thing after the other disrupting global trade, and the brands that aren’t able to respond and have fragile supply chains, which is the way that the traditional supply chain is organized, are the ones that are going to find themselves losing competitive advantage to the ones that are able to respond.”

Beauty Independent spoke with Benson on Friday about how brands will lose competitive advantages if they make the wrong supply chain moves, why he doesn’t foresee extensive reindustrialization, the reasons behind beauty’s newness slump, and the importance of multimodal supply chain networks amid volatility.

What did you see brands do when Donald Trump was elected to his second term last year?

We didn’t see a great deal change when he was elected. I was in the States going to a beauty conference after he was elected, and there was a bit of chatter more about the political situation, not about tariffs or trade. People are generally naively optimistic, especially when it comes to something that’s really hard to change like supply chain. You don’t want to change it if you don’t have to. So, we didn’t see a lot of movement.

My advice then was my advice now: We’ll help massively diversify your supply chain. We’ll multi-shore your products to maximize the outcomes and make sure you have inventory. Or do nothing. Wait and see because it’s so changeable.

A lot of people post-COVID supply chain shock had their China plus one policy. So, they went to Vietnam, Cambodia, etc. Trump turns around and Vietnam and Cambodia were two of the highest tariff places. A lot of people freaked out. Obviously, we have a 90-day moratorium on the rollout, but it’s feasible that comes back in the same aggressive way.

What we’re seeing now is there’s a lot of movement, and people are looking for a solution, but there’s no obvious path to a solution because, if you maintain a traditional supply chain structure, if you move your suppliers around, you just move the risk.

Let’s say that a scenario is you move your assembly supplier from China to Florida. You’ve taken an economic risk of tariffs and turned it into a natural disaster risk in terms of hurricanes. My opinion is, if you’re managing these traditional supply chain structures, you’re probably carrying too much risk, and it’s going to be extremely difficult in the future. I don’t think this current moment of tariffs is the final nail in the coffin of what is going to be decades of supply chain or trade volatility. That means that brands have to come up with a new solution.

Tell us more about what you are seeing from brands now.

Panic. We’ve got one American brand that’s around $500 million, and this week I probably received 30 emails from them with all their different products and components, asking us to help with all these things. I got on the phone with their COO, and I was like, “Tell your team to stop, and let’s sit down and have a strategic conversation about what to do.”

What we’re doing is helping brands multi-shore. A good example of this is a billion-dollar European skincare brand, and they had the prescience mid-last year to decide to multi-shore. We built a supply chain in the U.S. for them, and they have a supply chain in Europe servicing the rest of the world.

They manufacture U.S. goods in the U.S. and manufacture goods for the rest of world outside of the U.S. to maximize margin across the product range. That has advantages outside of maximizing margin around tariffs or tariff avoidance, but it also has that benefit as well. We’re doing a lot of that right now with brands.

If brands are looking to move manufacturing to the U.S., what are the capacity constraints they will come up against?

The U.S. is definitely capacity constrained. That said, there is still a lot of latent capacity in U.S. manufacturing. I spoke with the manufacturer a couple of days ago. We were able to tie up 40% of their capacity, which they had just sitting there. We didn’t outcompete someone for that. They were just running at 60%. So, there is capacity within that $44 billion.

That said, it is going to get competed away quickly. Are you familiar with the bullwhip effect? It has played out a lot over the last 10 years. It is an economic concept of how changes in demand can have massive effects upstream through the supply chain. We saw that with COVID where the ports got log jammed because consumer demand for buying goods went up, and road freight and the ports were at 100% capacity.

It’s not about the tariffs. It’s about how decisions that get made today are going to impact the supply chain because the supply chain is inflexible. So, what we’re going to see is a competition for the remaining U.S. capacity. As U.S. capacity reaches 100%, lead times will blow out and become unpredictable. Brands will have to order more inventory because now they’re waiting a lot longer. They can no longer do just-in-time manufacturing.

That means more of their capital is tied up in inventory, which means less capital for marketing and growth, which means that brands manufacturing in the U.S. become less competitive on the global stage, so their European competitors are able to outcompete them because they have more capital to spend on marketing and growth.

We’ve been hearing a lot of doomsday scenarios predicting a retail and manufacturing crisis in the U.S. later this year. Do you think that’s a likely scenario?

A lot of people right now are trying to read the tea leaves, and it’s extremely difficult to do. I always live by the expression, “The future is weirder and closer than you think it is.” I think consumer demand might come down 5% to 10%. I don’t think we’re going to have this complete implosion of our capitalist consumer system, and all the demand goes away and manufacturers are switching off their lights.

I also think that the reindustrialization narrative is not going to happen. It’s a 10-plus year process to industrialize the U.S. I think that we just go, OK, there’s fixed manufacturing capacity in the U.S., and the U.S. is still the biggest consumer market. If it dropped by 10%, it’d still be the biggest consumer market. Obviously, that would be a significant drop, but I think that there’s going to be a capacity constraint on manufacturing. It’s probably going to be a good time to be an existing U.S. manufacturer.

Would you open a U.S. beauty manufacturer today if you could?

I probably wouldn’t. It’s five years to spin up a plant. If I was a consolidating force, would I try to go and buy facilities? Potentially. I know that there are a number of private equity firms that are doing that right now.

The reality of a lot of manufacturing facilities is that they’re not really run efficiently. They’re not quite mom-and-pop operations, but they’re not professionalized. I think there is an opportunity for professionalization and to take advantage of this current moment provided that there are functional lines and machines, and there’s real estate, an employment base, an industrial commons that can serve that manufacturer.

How are beauty brands considering diversifying their supply chains?

There’s two dynamics right now. There’s what’s happening in the U.S. and then there’s the rest of the world because obviously the aggressive trade stance of the current administration is driving multilateral economic conversations in the rest of the world like EU and China are getting closer together. We’re seeing Korea, Japan and China having a multilateral trade conversation right now. A year ago, that conversation would never have happened.

I think there is going to be a favorable rest-of-world environment and an unfavorable U.S. environment for brands. The question, how do you respond to both those things? OK, you move out of China for the U.S. because of 145% tariffs, but do you get less competitive for the rest of the world?

Making a near-shoring or onshoring decision is still risky in this current environment. The decision that you have to make, in my opinion, is you need to move your supply chain to a network-based model where you have multiple redundancies across geographies, capabilities, etc. For any given SKU, that means that, whatever happens, you’re able to respond to that.

Like I said with the European brand example, we’re able to spin up a supply chain in the U.S. servicing the U.S. in four and a half months. Now they’re able to serve rest of the world through one supply chain in the EU and the U.S. market through another supply chain. If something happened and they said, “Now we need China,” we would be able to spin that up in three months because we have a network of capability and capacity around the world. This is what we’re going to see happen more and more throughout the supply chain because the technology to make this happen is only starting to become available right now.

If a brand is picking up the phone and saying, “Should I move my supply chain to Mexico?” I would say, “You can move your supply chain to Mexico, but you’re still carrying risk. If you do that, you need to be able to respond.” You need to be able to be responsive and dynamic in your supply chain organization.

Charlotte Palermino, co-founder of Dieux, mentioned on social media that indie brands’ lack of formula ownership is an impediment to them moving manufacturers. Do you see that as a big impediment?

Absolutely, that’s a problem. I’ll talk about why that dynamic exists. Manufacturers don’t care about the formula IP. What manufacturers care about is having a long-term relationship with the brand. They want to be able to develop a product and then continue to earn from that product over a long period. They hold the IP as leverage to generate that relationship.

That means that the manufacturer can effectively underperform, and the brand doesn’t really have a choice. That brand has to make that product with that manufacturer. That’s why a lot of beauty investors won’t invest in you if you don’t have the IP. There are exceptions to that, but that’s quite common.

All the brands that we work with own IP, that’s fine with us. We have the same needs as a manufacturer. We want a long-term relationship with the brand so that we can continue to earn all the products that we create, but we are highly confident that we’re going to perform. You can have the IP, and if we deliver what we say we’re going to deliver at the right costs on time, then you’ll keep manufacturing with us for a certain period. If we don’t, you’ve got the IP, and it’s written into the contract, and you can break and take the IP.

We have been going through a lot of reverse engineering of products in order to create optionality for brands, which is something that’s possible. That’s not necessarily easy to do, but we’ve been able to achieve that for brands. But not owning IP definitely represents risk for brands, and it makes it difficult for them to diversify.

The zoom-out is that your supply chain can be a constraint, or your supply chain can be a growth enabler. It’s really expensive to even set up a traditional supply chain, and it is not easy for a brand to do it. I feel for the brands that are locked into scenarios. As the world becomes more volatile, those constraints are going to become amplified. Trying to land on a constraint-free dynamic where your supply chain is a growth enabler and not a growth constraint is going to be important for the brands that survive and thrive in the upcoming increased volatility.

Are there other constraints like custom tooling, for instance?

A majority of products in the market don’t have custom tooling. They’re off-the-shelf components. Custom tooling represents a constraint, but you can recreate a mold. We do this for brands all the time. We will take the product, make the mold with a single manufacturer and then reproduce that mold for a couple of grand at another manufacturer. I don’t think that’s a particularly strong constraint. IP is probably the biggest constraint.

There’s a horror story of a brand that we don’t work with. This brand went to a big U.S. manufacturer, and they said, “We’ll give you 10% equity in the company, but you have to lower your MOQs.” Manufacturer said yeah, pays 10% equity. The brand then turns around and says, “Actually the business is going really well in Asia, we want to open up a new facility manufacturing in Asia because it doesn’t make sense for us to be manufacturing in the U.S. and then sending to Asia.” It asks, “Can we get the IP?” The manufacturer was like, “Sure, $20 million per formulation.” The brand has to then go and reverse engineer products.

Pre-2016, a lot of big skincare beauty businesses were built on the back of these kinds of relationships because you didn’t have to change your supply chain. These rigid structures would deliver for you, but that just doesn’t exist now. Reverse engineering is possible, but you should do it in a way that is going to create freedom for you.

Newness has decreased in the beauty industry. Why?

The thesis for our business is that the supply chain is so constrained that it is unable to move at the pace of culture, of consumer preferences. The way that supply chains are organized has been the same basically since the industrial revolution, but it solidified post-war. They’re slow, but that was fine when consumer preference liquidity was slow. It would take you three years to develop a product. That’s OK when you could rely on a decades-long payback period on that product because consumer preferences didn’t change.

So, the economics of new product innovation made sense, and then the speed of culture massively accelerates and the supply chain doesn’t change, but the consumer expectation changes. You’ve still got a 3-year development time, but you’ve got a consumer preference that’s changing every week or every month, and there’s no longer a reliable ROI on any new product innovation.

Brands have to make decisions, how do we move faster? What they do is product renovations, new colors for existing products, new packaging, duping. So, there’s a distinct lack of newness because it takes brands a long time to do new, and when they do new, it’s expensive, and there’s no longer a predictable and reliable ROI on that newness.

That’s what our entire business is built on: Four and a half months is our average time to market compared to three years. Then, how do we lower the cost of innovation to near zero such that there is no ROI burden on any new product that you create? It’s more of software-style product development.

You can launch products, test them with the market. The ones that go well, you can invest into aggressively and grow them, and the ones that don’t do well, you can deprecate, and you don’t have to pay back hundreds of thousands or million dollars on that innovation. Without fear, you can deprecate that product and invest in the ones that are working.

You mentioned that you don’t foresee the U.S. reindustrializing. What about other countries? Are there any green shoots of more capacity for beauty and personal care manufacturing in different countries?

We’re not seeing green shoots yet. It’s too early. It is so slow to create a facility. If you’ve got a manufacturing facility and you want to add a line, that’s real estate, machinery and training of people—a multi-year process. Then, you’ve got the industrial commons, which is the fabric of the market to provide the expertise, headcount, etc., to be able to operate.

The Australian industrial commons, for example, just doesn’t exist. There was a story here of a manufacturer who the government gave a grant of $10 million to open a new factory. They opened a new factory, and they can’t staff it, so it runs at 10% capacity.

What we are seeing from post-COVID and Donald Trump’s tariffs from the last term is Chinese manufacturers opening facilities in different regions around the world. The Chinese have been the most proactive in acquiring and building new facilities.

I would imagine it’s an irresponsible decision for someone to invest in a new facility in such a changeable environment. There’s no massive ordering of machinery. If you make the wrong investment into the wrong machinery, the market is going to kill your business. They’re extremely challenging businesses to operate.

For a hypothetical skincare brand that manufactures in South Korea, what should it be asking itself over the next 90 days?

Where do I see growth over the next five years? I would be trying to think on those timescales. Then, do I own IP? What is my current team’s capacity? How much resources do I have to take action? If the U.S. is a really important market to you and you’ve got capacity and IP, I would consider multi-shoring, opening a supply chain in the U.S. to deliver for the U.S.

If the U.S. is not that valuable to you—China is a larger importer of K-Beauty than the U.S. by a factor of two—if China is your growth sector, then maybe the U.S. isn’t going to be the market you thought it was. Compete where you can compete. Maybe it’s the EU.

I would be starting to consider what my 5-year goal is not, oh my god, how do I solve for the current tariff? It’s like, how do I solve for the ongoing volatility and work toward my 5-year goals instead of trying to solve for the next six months?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.